This analysis

was donated by Leaf.  Introduction Having started fencing about six months prior to seeing Utena for the

first time, it was perhaps no surprise to anyone that my favorite

characters were -- almost instantly-- Juri, and, much later, Ruka, the

captain and former captain of the Ohtori fencing club. I don't mean to

suggest that the only reason I like them is because they fence --

although it is rare to see portrayals of modern fencers in any sort of

visual medium -- but it seems to me that fencing, and the way they

fence, brings out certain aspects of their characters, just as the

interactions between Touga and Saionji in the dojo do.

Try to describe Juri and Ruka in a sentence or two without including

the word "fencing". It's possible to do, but you're leaving out quite

a bit. On or off the strip, both Juri and Ruka are skilled

perfectionists, respected, admired and feared for their talent and

technique. Fencing demands dedication, determination, agility and

speed, an awareness of one's adversary, as well as the ability to read

their body language and respond accordingly -- all of which Juri and

Ruka display over the course of the series.

Fencing is about following forms and conventions, rather than letting

emotions, feelings and innermost desires rule. Fencing is about

discipline and control, forcing one's body into unnatural positions.

(The fencing en garde stance is not a natural position -- it is one

that must be practiced for a long time before it becomes truly

comfortable.) Calculation, efficiency, concentration... all of these

traits are necessary if one is to be good at fencing. Doesn't this

sound like people we know?

While it's true that Miki fences as well, it is his piano playing that

defines his character, rather than his fencing. This is evident in the

fact that Miki's talent for the piano is brought out in every

Miki-centered episode, whereas we only see him fencing to serve as a

foil (pardon the pun) to Juri. If one were to strip Juri of her

skill, position and talent on the fencing strip, something fundamental

to her identity would have been lost. However, if Miki were not to

fence, I feel that his character would not change much. Fencing is key

to all of the Juri-centered episodes, just as piano playing -- not

fencing-- is key to Miki's.

As both a fencer and an Utena fan, I felt compelled to go through the

fencing scenes to see what I could learn from the tantalizingly brief

excerpts the series presents us with. And now for a short disclaimer:

though I fence foil, I am by no means an expert on the subject. I

don't claim for this to be an exhaustive analysis, either, but merely

a record of the details I find interesting and important. Also, given

the nature of the series, the focus is on symbolism, aesthetics, and

the personality of the participants, rather than achieving technical

accuracy in the animation. Nevertheless, analysis of the technical

matters isn't a waste of time; it often reveals some surprising things

about the show's characters, as I think we will find. And if *that*

isn't a critical to understanding the nature of Utena, I don't know

what is.

Tools of the Trade For those unfamiliar with fencing, there are three different weapons

in common usage, each with their own sets of rules, conventions and

quirks.

-Foil is the basic style, originally intended as a training mechanism,

though it gradually evolved into a sport of its own. In foil, valid

target area is the back and front of the torso. Points can only be

scored by hitting the tip of your weapon against your opponent's

target area. In addition, a certain convention known as "right of way"

exists, so that whoever extends their arm to attack first will get the

point if they touch, unless the opponent follows a certain procedure

to take the right of way back from them.

-In saber everything above the waist, including head, hands and arms,

is valid target. Like foil, right of way convention is followed, but

certain footwork moves are not allowed, and slashing is legal.

-Épée, like foil, is a point weapon, but all parts of the body are

valid target area, and the right of way convention does not exist.

Épées can be distinguished from foils by their extended bell guards,

which serve to protect the weapon hand, which is not valid target in

foil. Historically, the modern épée is descended from the rapier, a

long thrusting weapon developed in Europe around the 16th century.

(For those still unclear on the distinctions, pictures and more

information can be found here.)

In the Ohtori fencing club, all of the weapons I can see appear to be

épées. Some of the fencers in the background might be carrying foils,

but since they are so far away, these could easily be epées as well --

it's hard to tell from a distance. Certainly in all of the close-up

shots, Juri is holding an épée, as is Miki. We the viewing audience

can observe this quite clearly right before Juri sends his blade

flying onto the balcony during the Black Rose Arc. In the Ohtori fencing club, all of the weapons I can see appear to be

épées. Some of the fencers in the background might be carrying foils,

but since they are so far away, these could easily be epées as well --

it's hard to tell from a distance. Certainly in all of the close-up

shots, Juri is holding an épée, as is Miki. We the viewing audience

can observe this quite clearly right before Juri sends his blade

flying onto the balcony during the Black Rose Arc.

It's also worth pointing out that all of the weapons we see being used

at Ohtori are French grips, rather than the more modern pistol grips.

This makes sense on several counts. One, anyone can use a French grip,

as long as it's tilted for the appropriate dominant hand, so it's

something more commonly seen in club settings, where a lot of people

are coming and going, and not everyone has their own equipment. But

even Juri, who certainly should own her own weapons, has a French grip

on her épée, indicating that it's not just convenience that's the

issue here, but something that strongly points to the philosophy of

the club, and of Ohtori Academy as a whole. More on this in a second.

My inclination is that Juri, although undoubtedly skilled in all three

styles of fencing, is primarily an épée fencer. This would make sense,

given the amount of skill and dexterity necessary to specialize in

epée, and the nature of the duels, where hits on any part of the body

are permitted -- although in those duels, the only hit that matters is

knocking the rose off of the opponent's chest. In many ways, épée is

the least limited of the modern fencing styles, with no right of way

convention and no restrictions on target area. Both aspects would make

the study of épée an ideal choice for the dueling arena.

What about Ruka? Ruka, however, is another matter entirely. Ruka is using a "special"

weapon, one that looks distinctly different from the épées that Juri,

Miki and the other fencers are using. Ruka isn't using a part of the standard repertoire of modern fencing

-- Ruka is using a rapier. Other students, including Juri, are not

shown using this in the club. This is important.

As mentioned earlier, the rapier is a long, thrusting weapon that

eventually evolved into the modern épée. Rapiers are distinguished

from épées by their complex, ornamental hilts, often with a slender

curve of metal coming down from the bell guard to the pommel. Ruka's

rapier has a decorative quality that all the other weapons lack. This

is intended not merely to be functional, but beautiful as well. It's

also pretty damn distinctive -- for one thing, it's golden, while all

of the other weapons are silver-colored. It would be impossible for

anyone with any knowledge of fencing whatsoever to mistake his sword

for anyone else's. This is going to prove important later on, when it

comes to Shiori.

Why is Ruka fencing with a rapier when Juri and the others are fencing

with épées, anyway?

Style I mentioned earlier that there are three different weapons commonly

used in fencing. There are also several distinctive styles or schools

of fencing. Although there are countless variations, all of them can

be roughly grouped into three major categories: historical, classical

and "sport" fencing.

Historical fencers attempt to re-create what fencing looked like

before the development and proliferation of the foil, saber and épée.

Classical fencers, on the other hand, use these three weapons, but try

to fence in as martially accurate a manner possible -- that is to say,

as if one were fighting a real duel with sharp weapons. In sport

fencing, however, the goal is to score as many points as possible

while staying within a stringent set of rules. This last kind of

fencing is the most prominent style today, and is the kind you'll see

at intercollegiate events and the Olympics.

If the architecture of the school and the 19th-century military-style

outfits (complete with epaulets) worn by the members of the Student

Council weren't enough to give it away, it's pretty easy to tell that

the Ohtori Academy fencing club follows the classical school.

For one thing, in classical fencing, the object is to touch the other

fencer without being touched. That's it. If you get touched, you've

lost, because in classical fencing, that sword your opponent just used

was sharp enough to kill or incapacitate you. This is why Juri is able

to go through so many opponents so fast. In sport fencing, though,

bouts are usually fenced to five or fifteen touches, and the person

who gets the most touches wins the bout. We don't see anything like

that here.

Another clue is that we never see any wires or electric scoring

machines being used in the fencing bouts. Outside of practice, all

sport fencing bouts are scored with these machines, which means that

participants have to attach wires to themselves and their weapons in

order for that machine to be able to register their touches. Unlike

sport fencing, which has undergone numerous changes over the years as

technology has improved, classical fencing has stayed relatively

unchanged since the early 1930s or so, since it uses the judgments of

a human being rather than a machine. This explains the proliferation

of French grips, rather than the newer pistol grips we see on the

épées.

Classical fencing also would explain why Ruka is using a rapier

instead of an épée. This would be both highly unusual and against the

rules of modern sport fencing, where the rapier is no longer used. In

classical fencing, however, there would be no such bias. It would

still be a somewhat unusual choice, though and it would certainly be

much harder to come by than a standard épée.

A final indication is that Juri and Ruka both are using the classical

stance in their en garde position -- non-weapon hand held curved up

with hand held up behind them. While a lot of sport fencers do this as

well, many do not, and its use is considered a sign of at least a

little classical training.

What's the significance of their use of the classical style? For one

thing, it fits well with the background and philosophy of Ohtori

Academy. For another thing, classical fencing treats fencing like a

martial art -- that is, for use in actual battles with real blades --

instead of just a sport. In baseball, if the opposing team gets a home

run, it doesn't necessarily mean they've won the game. In classical

fencing, if your opponent touches you, you've lost and there's nothing

you can do about it. This makes excellent preparation for the duels

for the Rose Bride, as Utena is never able land any sort of touch on

Juri.

Classical fencing is also more concerned with aesthetics than sport

fencing. This isn't to suggest that sport fencing completely ignores

aesthetics, but it is true that aesthetics, technique and perfection

are more heavily emphasized in most schools of classical fencing. And

you've got to admit, aesthetics certainly matter at Ohtori, and in the

series as a whole.

Day to Day in the Ohtori Fencing Club What is life like for the fencers at Ohtori? We only get to see a few

moments, but even those are enough from which to draw some

conclusions.

First of all, who fences at Ohtori? Although it's hard to distinguish

gender when the fencers are masked, there seems to be more females

fencing at Ohtori than males.

There are a ton of unmasked girls in fencing whites hanging around

when Ruka is running the club, (although how many of those girls have

just joined since Ruka's arrival and how many leave after he

disappears is unclear). But even at the end of Episode 29, after Ruka

has left the school for good, we are shown a group shot of a room full

of unmasked fencers, the majority of which seem to be girls. Finally,

in the last episode, all of the unmasked fencers surrounding Shiori

are female. This is not to say that there aren't any guys fencing at

all -- there's Miki, Ruka, and one unnamed boy who retrieves Miki's

épée from Anthy into Episode 17 -- but from what we're shown, the club

is mostly, if not entirely, female.

This makes sense when we consider how much the female population of

Ohtori admires Juri. (She always merits a respectful "senpai" from

Utena, which should say something.) I imagine many guys might find her

quite intimidating... and certainly, having Ruka as captain, with the

hordes of adoring fangirls, is much more likely to attract women than

men.

Practices usually start with warm-ups, stretching and footwork

exercises, before proceeding to blade work and bouts. Most of what we

see in the club setting are bouts between Juri and the members of her

club, although occasionally we catch a glimpse of her teaching, as

well. ("Don't forget the trick I just showed you.") We also see Ruka

coaching people on the basics of hand and body positions in Episode

28.

(Speaking of Ruka, the en garde position that Ruka and the girl are in in

that scene is pretty terrible, actually. The

front foot should be facing forward, while the back leg should be at a

ninety degree angle to the front foot and slightly off to one side.

Given the position of her legs, she's probably intending to be in a

lunge position. All we hear Ruka tell her is to close her stance more,

and tilt her hips. I'd probably tell her to fix her feet and hold

herself more upright -- she looks like she's slouching a lot, even in

her lunge. Then again, she's a novice, and Ruka's feeling her up. I'd

probably find it hard to keep my balance in that kind of situation,

too.) The

front foot should be facing forward, while the back leg should be at a

ninety degree angle to the front foot and slightly off to one side.

Given the position of her legs, she's probably intending to be in a

lunge position. All we hear Ruka tell her is to close her stance more,

and tilt her hips. I'd probably tell her to fix her feet and hold

herself more upright -- she looks like she's slouching a lot, even in

her lunge. Then again, she's a novice, and Ruka's feeling her up. I'd

probably find it hard to keep my balance in that kind of situation,

too.)

Practices seem very formal and follow strict procedure. Juri mentions

the existence of a definite schedule, and Ruka's first appearance is

as a disturbance of the normal order of things – Miki was supposed to

fence next. At the ends of bouts, there is applause and the obligatory

"Arigatou gozaimasu!" from the defeated opponent. It's clear from her

tone of voice as she yells "Next!" and her rebuke to Miki in "Thorns

of Death" that Juri can be a hard and demanding taskmaster.

Yet for all that, she truly cares about her fencers. When a girl is

injured at the end of "Azure Blue Paler than Sky," Juri is the one who

takes her to the hospital and reassures her anxious worries. She even

tells the girl not to push herself, that healing is the most important

thing to focus on at the moment. Juri may be imperious, but she takes

her responsibilities as captain seriously. As Nanami aptly puts it,

"There's nothing to worry about with Juri in charge."

The girl also mentions an upcoming local meet, which indicates that

the fencing club might participate in events with other schools as

well. While competition is not the focus of classical fencing, her

comment indicates that the club belongs to a local or regional

classical fencing league with other rich, private high schools, which

would be uncommon, but not unheard of.

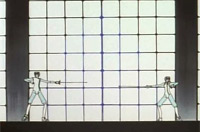

Juri and Ruka's first bout (Episode 28) Ruka is definitely left-handed. He put his glove over his left hand,

and when facing a right-handed Juri, their weapon hands are on the

same sides of their bodies. (If

Juri were left-handed, their weapons would on opposite sides of each

other.) From an animator's standpoint, this is the most aesthetically

pleasing position, since we can see the front of both fencers, whereas

if they both were right- or left-handed, the body of one would be

facing away from the audience. From a tactical standpoint, it means

that Ruka is going to have at least a slight advantage over Juri, as

left-handed fencers are not as common as right-handers, and are most

easily able to get around their right-handed opponent's en garde

position (parry six) unless their opponent takes special precautions

against them. aesthetically

pleasing position, since we can see the front of both fencers, whereas

if they both were right- or left-handed, the body of one would be

facing away from the audience. From a tactical standpoint, it means

that Ruka is going to have at least a slight advantage over Juri, as

left-handed fencers are not as common as right-handers, and are most

easily able to get around their right-handed opponent's en garde

position (parry six) unless their opponent takes special precautions

against them.

We don't get to see very much of this bout -- most of the time is

spent watching the reactions of Miki, Anthy and Utena. We do, however,

see Juri retreat as Ruka attacks, before Ruka continues pressing his

attack and Juri rushes forward to attack. The camera pans out to show

both Juri and Ruka in lunge position with their arms extended. We then

see that Ruka has touched Juri. The entire sequence takes about

fifteen seconds, which is not atypical in fencing.

The one noteworthy thing about Ruka's touch is that he hits her on her

left breast, exactly where her rose would be if she were fighting in

the duel arena. Coincidence? Perhaps. Perhaps not.

Whose Sword is It, Anyway? I am now going to take this opportunity to make a claim that will

contradict what many people believe about the end of Episode 28 That

is to say, we "know" that the sword that Shiori claims to be polishing

isn't Ruka's, but Juri's. We know the first bit because Ruka says it

wasn't his sword after all, and we generally assume the second part

because his locker is shown as being right next to Juri's.

Except Ruka's lying.

Nobody else in Ohtori is using a weapon like Ruka's. It's flashy. It's

pretty. It's distinctive. But we never see anyone else in the entire

series -- even Juri -- use anything like it. And it's pretty obvious

that the sword that falls out of the locker is identical to the one

Ruka used in his bout with Juri earlier in the episode. This means

that either

A) Ruka is lying to Shiori when he tells her that it wasn't his sword

to begin with

B) Somebody else (most likely Juri) *has* a sword like Ruka's, but never

uses it

C) The animators didn't know what they were doing, and assumed that

all weapons looked like that

Option C is out because it's pretty obvious that the animators know

what épées are supposed to look like, as discussed above. Option B is

possible, but what's the point of insinuating to the audience that

it's actually Juri's sword when we never see her using any weapon like

that? Therefore Option A is the most likely explanation. When Ruka

tells Shiori at the end of his duel that it wasn't his sword that she

had claimed she polished every day during his absence, he is lying

through his teeth in order to break her.

And, really, doesn't that fit with all of his actions towards her?

Build her up, lie to her, and then -- completely and totally crush

her, both mentally and emotionally. That doesn't sound out of

character for Ruka at all, to use whatever means necessary --

including lies -- in order to accomplish his goal of saving Juri from

Shiori, and from herself.

Watching the locker room sequence, I think, supports this. Shiori

walks past Juri's locker, and runs her fingers against  Ruka's

nameplate, and is then shown leaning against a locker whose nameplate

we can't see. Ruka startles her, she turns -- and in that split

second, you can see the nameplate on the locker she's leaning against,

and it's Ruka's name. (It flashes by really fast, so it's hard to see

even when you're looking for it. Nevertheless, it's definitely there.

) Regardless of whether she was leaning

against Juri or Ruka's locker, the nameplate of the locker her hand

hits is definitely Ruka's – because the sword that falls out is

definitely his. Ruka's

nameplate, and is then shown leaning against a locker whose nameplate

we can't see. Ruka startles her, she turns -- and in that split

second, you can see the nameplate on the locker she's leaning against,

and it's Ruka's name. (It flashes by really fast, so it's hard to see

even when you're looking for it. Nevertheless, it's definitely there.

) Regardless of whether she was leaning

against Juri or Ruka's locker, the nameplate of the locker her hand

hits is definitely Ruka's – because the sword that falls out is

definitely his.

Ruka obviously didn't expect Shiori to notice the difference between

his weapon and all of the others, as a more experienced fencer would.

Then again, even if she did notice, she was evidently in too much

shock after being thrown through the windshield of an Akio car to call

him on it.

In any case, given the significance of this particular sword in their

relationship, it's especially apt that the sword Shiori draws from

Ruka's chest is identical to the sword he uses to fence Juri, and the

sword that falls out of his locker. We only get one quick look at its

distinctive hilt -- right when she's pulling it from his chest -- but

even in shots from other parts of the duel, it's pretty clear it's the

same sword in all three cases. Viewed through this lens, the locker

room sequence suddenly takes on a whole new meaning.

Postscript: After the Revolution Given all that I've implied about the significance of fencing in the

lives of the characters, a new question emerges at the end of Episode

39: Why does Shiori fence?

It's perplexing, when you stop to consider it. Aside from her romantic

attachments to various club members, Shiori has never shown any

interest in the actual act of fencing (claims of polishing swords

aside). And yet, suddenly we see her among a cluster of girls clad in

fencing whites, a smile on her face as she acknowledges Juri's

imperious "Next!" How did this come about?

I take this to mean that Shiori has stopped wanting to bring Juri down

– instead, she wants to become like her. All her life, she's watched

Juri from the sidelines, and as a result, she has been continually

enveloped in a stew of malice, jealousy and self-loathing. Now she has

taken the first steps to becoming a real human being instead of a

vicious parasite by actively working to achieve skill and competence

at something, rather than being held back by her envy of Juri's innate

talent. The only way to have freedom is to know oneself, and the only

way to know oneself is through hard work and discipline, and fencing

requires both. (Why then does Juri still need Ruka's help to get free

of Shiori? Because it's not that Juri doesn't know herself; she just

doesn't think that it's possible for her to change, which is an

entirely different problem.)

It's clear at the end of "Azure Blue Paler than Sky" that things have

changed between Juri and Shiori. How would Shiori respond to such

treatment? Without Ruka around, and with Juri suddenly immune to her

manipulations, perhaps Shiori is attempting a new beginning.

And even if that's not true, if Shiori hasn't changed, and her fencing

is still just a ploy, it won't work. When the locket shattered, Shiori

lost all power over Juri. But I prefer to believe that even Shiori, who acts not to advance any

particular agenda of her own, but only to cause pain in others, is

capable of changing for the better, of acquiring a purpose of her own

-- something worth fighting for. I choose to interpret

the final fencing scene of "Someday, Shine with Me" as supporting this

idea.

|