This analysis

was donated by Jude Deluca. (Link to Twitter.)

Also check out Comicosity and Point Horror!

Do you know? Do you know? Have you heard this story before?

A pink haired young girl seeks to protect her friend, a bullied young woman with a bindi mark on her forehead. What the pink haired girl doesn’t realize is there’s more to her friend then she’s able to recognize and the girl with the bindi mark is not so innocent…

Reading that, you’d think I’m talking about Revolutionary Girl Utena, the manga created by Chiho Saito that was later adapted into a 39-episode anime by Kunihiko Ikuhara and Be-Papas. Revolutionary Girl Utena, the story about Utena Tenjou, a girl who wants to become a prince and gets entangled in a mysterious dueling game centered around Anthy Himemiya the Rose Bride.

Well, guess what? I’m talking about a story that was released at least two decades before Utena was ever a thing! I’m talking about Sukeban Deka.

Revolutionary Girl Utena’s been one the series I’ve followed ever since adolescence. It and Sailor Moon are the two animes I’ve consistently devoted time and attention to for decades, and it’s sort of influenced a lot of my story ideas. I’m still learning new things about Utena thanks to bloggers such as rosepetalrevolution, ladyloveandjustice, and docholligay of Tumblr whose respective liveblogs of the anime have opened up interpretations I never would’ve considered on my own. Speaking also as a comic book fan, I have to say Utena is by far a much better crafted deconstructionist story compared to the hype and legend of DC Comics’ Watchmen. Utena deconstructs the toxic elements of fairy tale motifs, abusive and incestuous relationships, internalized homophobia, and the Madonna-Whore Complex. At the same time, it manages to get the viewers to develop sympathy for largely disgusting characters in ways I still assert Watchmen failed. I don’t mean this a matter of being pretentious, I truly feel for as weird and confusing it could be, Revolutionary Girl Utena’s a really, really good story.

As an Utena fan, I felt this was my opportunity to finally contribute to the fandom by discussing the eerie similarities between it and this story about a delinquent girl detective.

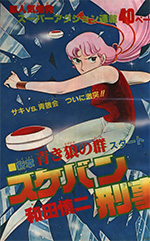

Sukeban Deka was created in 1975 by artist Shinji Wada. The story was serialized in “Hana to Yume” as a shoujo series for six years. During the 1980s it received a television adaption, followed by an OVA in 1991 (link to YouTube trailer) and three live action films. However, Sukeban Deka has sadly remained something of a niche interest among anime and manga fans. Those who know of it have likely either watched the OVA, which was dubbed in English and distributed by the now defunct ADV Films, or are tangentially aware of the TV show. Studio Trigger even went as far as to do an extensive homage to Sukeban Deka’s first season end sequence in Kill la Kill. Thankfully, dedicated fans have been methodically translating Wada’s original stories into English and posting them online for all to read.

The Premise: Saki Asamiya’s a delinquent doing hard time in a reformatory, and she’s content. Why should she have to deal with the outside world and all its ridiculousness? One day, Saki is approached by a mysterious man known only as Inspector Kurayami, or “The Dark Inspector.” He works for the Japanese police force and has a shocking offer for Saki. Kurayami wants Saki to become an undercover agent investigating crimes going on in Japan’s school system which is an area regular police agents aren’t able to enter so easily. Saki finds the idea laughable until Kurayami pulls out two notices. One will delay her mother Natsu’s impending execution on death row, while the other will speed up the process. With her abusive mother’s life hanging over her head, Saki angrily agrees to Kurayami’s proposal and becomes the Sukeban Deka. Since she can’t carry a gun, Kurayami has a special weapon tailored to meet Saki’s particular skills. Saki’s given a yo-yo made from bulletproof ceramic with an unbreakable string, and it also conceals her badge as a detective. From there, Saki becomes immersed in the sinister underbelly of Japan’s education system and works to expose crimes such as kidnapping, drug running, and even political corruption.

Basically, Saki’s a delinquent who goes around fighting crime with a yo-yo. The concept’s as ingenious as it is simple and bizarre.

Aside from the infectious imagery of Saki and her yo-yo, the other prominent aspect of the franchise as a whole is her archenemy, Remi Mizuchi. Deceptively designed to look like the heroine of a typical shoujo story, Remi’s a gleefully depraved megalomaniac basking in the glory of her own wickedness. The daughter of politician Gozou Mizuchi, Remi and her sisters Ayumi and Emi are introduced as the villains of Sukeban Deka’s first big arc where she orchestrates their deaths to get her father’s resources to build her own criminal empire. The OVA adapted Remi’s introduction and she was featured in the TV show’s first season, making her one of the few consistent elements to appear across Sukeban Deka’s various adaptations. She’s essentially the Joker to Saki’s Batman.

Labeled a shoujo manga, Sukeban Deka’s still loaded with violent imagery and frequently unhappy endings for many of its characters. People get mutilated, women are raped, and there are more than a couple of stereotypical depictions of Black characters which have not aged well at all. A frequent trend involves Saki befriending some young woman who eventually dies horribly after it’s revealed the other girl may have romantic feelings for her. This is a side representation of the “Compulsory heterosexuality” trope found in a lot of early shoujo stories (another example would by Riyoko Ikeda’s Oniisama E…), where queer women are either punished or kill off or their roles end after they marry men. Remi Mizuchi is even referred to as a dy*e by her sisters and accused of wanting to take over their school so she can have her way with young girls. It all offers a stark contrast to how Revolutionary Girl Utena was developed some twenty years later and its more, shall we say enlightened views on homosexuality. One must wonder how Utena would’ve gone if it was made in the same era as Sukeban Deka.

It was thanks to the good people of Empty Movement, a substantial Utena fansite running for years that “Witch Hunt” and “Cinderella’s Counterattack” initially came to light among the Utena fandom. Someone on their forum posted scans from the chapters in the original Japanese format with a summary of the events, highlighting the initial similarities with Revolutionary Girl Utena. For years I’ve been wondering if I’d ever get the chance to read this chapter in Saki’s adventures. The entire reason why I ever gained an interest in Sukeban Deka was after watching the OVA’s trailer and realizing how similar Saki looked compared to Utena Tenjou. Since the arc’s now been posted in English, the ability to read it in its entirety can allow for a deeper analysis of the similarities between it and Revolutionary Girl Utena.

“Witch Hunt” and “Cinderella’s Counterattack” focus on Saki learning Kyoko Himuro, her best friend from middle school, is suspected of murder. Saki gets enrolled in the prestigious Shirayuri High to investigate the death of Etsuko Muto and reconnect with Kyoko. Kyoko’s been attending the school on a scholarship, which means she has to work as a maid in her dormitory. She’s generally treated like garbage by most of her classmates, especially Eri Hanabusa and Yumika Daimon. Saki learns these two as well as the departed Etsuko are referred to as “Rose People,” meaning they come from families so wealthy even politicians answer to them.

Kyoko had apparently been bulied severely by Etsuko, Eri and Yumika for over a year and it got especially bad before Etsuko died. The three girls were all trying to woo Mitsuhiro Minowa, a young alumnus of Shirayuri and an incredibly successful jeweler whose family’s wealth puts theirs to shame. Things become complicated when Saki discovers Kyoko is also involved with Mitsuhiro, alongside evidence that indicates Etsuko tried to kill Kyoko. Only it seems Kyoko turned the tables on Etsuko. Saki refuses to believe her once dear friend would harm anyone and digs deeper into Etsuko’s actions prior to her death.

Saki finally exposes the twisted details of Etsuko’s demise to the girls of Shirayuri and clears Kyoko’s name. It turned out Etsuko had no idea Kyoko was involved with Mitsuhiro. Her real targets were none other than Eri and Yumika, who DID know Kyoko was after their object of desire. Etsuko wanted to kill her supposed friends by lacing their facial cream with potassium cyanide she got from one of her family’s industrial plants. To look innocent, Etsuko even put cyanide in her own cream so everyone would think the same person who killed Eri and Yumika was after her too. Etsuko was done in by stupidity when she mixed up the jars and applied the tainted cream to her face by mistake. The cyanide went into effect more slowly, and Etsuko fell to her death while performing in the school play.

Kyoko reveals she found out about Etsuko’s attempt to murder Eri and Yumika, so she stole the tainted jars from them before anything happened. When Etsuko died during the play, Kyoko deduced it was the cyanide and switched Etsuko’s cream jar with a non-tainted one before anyone found out. Saki demands to know why Kyoko went so far to protect Etsuko’s name, why she allowed everyone to point the finger of blame at her. Kyoko breaks down in tears saying she protected Etsuko’s memory because she didn’t want to believe a person who loved Mitsuhiro could be so bad.

Except for Eri and Yumika, everyone is touched by Kyoko’s compassion for someone who didn’t deserve it. Mitsuhiro’s so moved by this he apologizes for not revealing their relationship to the world sooner and grandly announces to everyone he’s marrying Kyoko. The girls of Shirayuri cheer and Mitsuhiro thanks Saki for proving Kyoko’s innocence…

Exactly as Kyoko planned.

Yep, Kyoko DID kill Etsuko Muto and set up a string of events to look guilty so Saki would clear her name. Kyoko manipulated everyone into thinking she was a demure, selfless Cinderella by bravely shielding Etsuko’s supposed murderous plan. Unfortunately for Eri and Yumika, their unrelenting pursuit for Mitsuhiro only gives Kyoko ample opportunity to make them suffer as well. For added measure, Kyoko murders one of the maids in the Minowa household, the one who’d been reporting to Eri and Yumika about Kyoko and Mitsuhiro’s relationship. Kyoko tricks Yumika into having a bunch of goons mutilate Eri’s face beyond recognition, then has Yumika’s pet dog infected with rabies so it’ll kill her.

While Kyoko’s getting rid of her two rivals, it looks like she was in the middle of planning something else. Two things end up standing in her way:

That Saki had been suspicious of the seemingly happy ending “Cinderella” received all along. Kyoko is actually dying from cancer, which has progressed so badly she only has a few months left to live.

Those sharp instincts Kyoko condescendingly applauded turned out to be true, as Saki had been left with a nagging feeling ever since the end of “Witch Hunt.” She passive aggressively tells Kyoko she knows the identity of the person manipulating everyone, but doesn’t outright say Kyoko’s name. Saki is still hung up on the Kyoko of the past, the one who had a light in her eye and dreamed of becoming a defense attorney. That doesn’t stop Saki from preventing Kyoko’s attempt on Mitsuhiro’s life, which leads to a chase through the woods until Saki finally corners a weakened Kyoko. Kyoko makes it clear she feels no guilt for destroying Etsuko and the others, arguing the three girls probably destroyed many more lives in their time. She has no tears to shed over the people who tried to ruin her happiness. However, Kyoko declares she’s always loved Saki far more than she did Mitsuhiro, kissing Saki and calling her a prince. Kyoko says she’ll give herself up, since she doesn’t have that much time anyway. Saki runs back to the Minowa mansion to get help…

As soon as Saki’s far enough away, Kyoko activates a detonator and kills herself in an explosion.  Seeing the fire rage, Saki can only ask how things would’ve gone if she’d remained friends with Kyoko all these years? Saki asks why she didn’t tell Kyoko she was her friend, why she didn’t tell Kyoko she remembered the hopes and dreams Kyoko once had. That these things remained unsaid and unheard may have turned Kyoko into a witch, but how are witches born? By the grim reaper of death, or of hearts seeking love?

As a side note, Shinji Wada mentions at the end of the volume how Kyoko was considered to be THE villain of Sukeban Deka’s second arc following Remi Mizuchi’s supposed demise. It didn’t work out as he wanted, since he claims Kyoko wasn’t properly motivated to fight Saki the way Remi was motivated. It would’ve been interesting to see Saki and Kyoko continually go head-to-head, possibly offering a look at how Utena might’ve gone if Utena and Anthy directly fought one another (beyond a sequence in the opening theme).

That’s a lot to break down for comparisons, but now that the story’s been properly recapped let’s begin. The first similarity everyone immediately brings up between Utena and Sukeban Deka involves the physical appearances of the lead characters. Saki and Utena both have long, pink hair while Anthy and Kyoko both bare bindi marks on their foreheads. Saki and Utena both dress in boyish clothes (although fans keep pointing out Utena’s not actually wearing the Ohtori’s boy uniform). Kyoko actually carries more of a resemblance to Anthy’s design from the Utena movie, Adolescence of Utena.

The prince/princess/witch dynamic is perhaps the biggest part fueling the similarities between the stories. Kyoko repeatedly describes Saki as being cool and strong, just like a prince. Utena Tenjou’s greatest goal was to become a prince like the one she met when she was a child, and many of the girls of Ohtori Academy believe Utena’s cool and amazing. Kyoko plays the roles of the victimized princess and the scheming witch, exuding the image of a put-upon damsel being abused by those around her when in reality she is passive-aggressively manipulating people into helping her cast this image. It looks as though she needs to be saved by both Saki and Mitsuhiro, who both fill the “Prince” quota for this story.

Anthy Himemiya is the Rose Bride, the object of winning the dueling game at Ohtori Academy so those who are “Engaged” to her can try and gain the power to revolutionize the world. Outside of that, Anthy is bullied and degraded by nearly everyone around her. Barely an episode of Utena goes by where she’s not slapped for something. People accuse her of having no will of her own and she’s seen as nothing but a tool. Utena believes she needs to save Anthy because she thinks Anthy wants to be a normal girl, not realizing until much later in the game that Anthy is far from helpless. She’s had an active hand in manipulating the other duelists and frequently gets revenge through subtle, passive-aggressive tactics. Both Kyoko and Anthy are accused of being witches and have the title foisted upon them by those who mock them.

Anthy’s dark skin and bindi mark, alongside Kyoko’s bindi mark, coupled with the bullying they receive also represents an undertone of racism motivating their attackers. Anthy suffers the most physical violence out of every character in Utena, up to and including getting stabbed in the chest by her brother in the movie.

The conflict between Kyoko and the three Rose Girls feels like the same spirit behind the Ohtori Academy dueling game. The four girls are essentially fighting one another to become engaged to Mitsuhiro Minowa, whose family is obscenely wealthy. The Student Council of Ohtori Academy are dueling each other to gain the Rose Bride, who is the key to gaining the power of revolution. Whereas the Student Council duel each other with swords, Kyoko and the Rose Girls fight each other through manipulation, intimidation, and murder.

The way in which Kyoko dispatches of Yumika Daimon feels like an especially dark exaggeration of the Utena episodes focusing on Nanami Kiryuu. Nanami’s the younger sister of Student Council president Touga Kiryuu, and her obsession with her brother is treated as both comedic and truly unsettling. Several episodes focus on Nanami and Anthy and involve the use of animals. Episode four, “The Sunlit Garden – Prelude,” features Nanami repeatedly trying to humiliate Anthy by hiding animals inside Anthy’s room to make her seem weird. The thing is, Anthy’s ALREADY hiding animals in her room and it only makes her seem cute because it shows she has a soft spot for them. The episodes “Cowbell of Happiness” and “Nanami’s Egg” reveal Anthy’s tendency to name barn animals after Nanami in what could be a form of sympathetic magic. The two episodes focus on Nanami receiving a cowbell she proceeds to wear on her neck at all time thinking it’s a fashion statement which then turns her INTO a cow, and Nanami waking up to discover an egg in her bed which she thinks she laid. Both episodes made it clear Anthy set up these events in order to screw with Nanami’s head, as revenge for the times Nanami’s had her lackeys smack and abuse Anthy.

Kyoko’s gambit to murder Yumika involved a stray dog Yumika took in. Kyoko gets her henchmen to have Yumika’s dog bitten by a rabid one, so Yumika’s will contract rabies too. The dog is unleashed on the day Kyoko visits Yumika’s home regarding evidence Yumika’s gained of Kyoko’s duplicity. Kyoko pushes Yumika’s buttons and gets pushed into Yumika’s pool, at which point the dog’s released and attacks. Kyoko’s safe in the water while Yumika’s dog savagely bites her shoulder and she breaks its neck with her bare hands. While the servants are rushing to get Yumika to the hospital, Kyoko destroys the evidence in Yumika’s bedroom. For added cruelty, the surgery needed for her shoulder meant Yumika didn’t get her rabies shots in time and dies two weeks later from the disease. Kyoko’s usage of animals and exploiting someone’s baser instincts to commit such a fiendish act almost makes Anthy’s manipulations seem tame by comparison.

But we have to go deeper…

Go deeper…

One of the biggest points of comparison I’ve come upon between the Utena/Anthy and Saki/Kyoko dynamics regards the perceptions of Utena and Saki. While Utena’s goals of wanting to be a prince and save Anthy seem admirable on the surface, Utena originally focused on rescuing the image of Anthy she created. Utena THINKS Anthy wants to be saved from the other duelists, she THINKS Anthy wants to be a normal girl. Utena’s motivated by her own ego and desire to have someone to save, so this is what she perceives Anthy to be.

The show’s third episode, “On The Night Of The Ball,” does a good job at demonstrating Utena’s denseness about Anthy’s wants and needs. When the two are invited to the spring dance, and Anthy’s told she’s been nominated for “Dance Queen,” Anthy turns the invitation down. She says she doesn’t like gatherings with big people because it feels like everyone’s watching her and it makes her uncomfortable. Despite her very clearly making her feelings known and showing right off she is NOT an emotionless doll, Anthy’s explanation is pushed aside by Utena’s stubborn belief Anthy needs this. She NEEDS to go to the dance because she NEEDS to make friends with people. So of course Anthy goes, gets humiliated, and Utena has to step in save her.

The further into Revolutionary Girl Utena we go, the more we learn about how unhappy and bitter Anthy truly is due to all the pain she’s suffered in her incredibly long lifetime. The dueling game at Ohtori and the search for the power to revolutionize the world were all born when Anthy tried to protect her brother, the prince known as Dios, after he ran himself ragged trying to save everyone and almost died. The people of the world were horrified at Anthy “Sealing away” their prince and called her a witch, running her through with swords which took on a life of their own. For possible millennia, Anthy’s been stuck taking all the hatred of the world as the Rose Bride while her disillusioned brother became Akio Ohtori, a.k.a. End of the World, and set up the dueling game to find someone who could recover that lost power. Since then, Anthy’s been part of a co-dependent, abusive, semi-consenting incestuous relationship as she and her brother kept finding more duelists to manipulate. It turns out the prince Utena met all those years ago as a child was Akio, and what really motivated her to want to be a prince herself was when she saw how much pain Anthy was in. She had no idea this chance meeting was set up by Akio to manipulate her into becoming the tool he needed to become powerful again.

As Utena begins to see more of Anthy’s true self, Utena begins to realize how badly she’s handled wanting to help Anthy all this time. Utena eventually confesses she never bothered to look and see how much pain Anthy was in because it would’ve required her to acknowledge her own hand in the matter, and she thus begs for Anthy’s forgiveness. Even as Anthy’s begging Utena to forgive her for using her. By the end of the show, Utena’s literally been stabbed in the back by Anthy yet still does everything she can to reach out to Anthy and help her escape the cycle of abuse she’s been stuck in for centuries. Even for all the ways Utena and Anthy consciously and subconsciously hurt one another, Utena understands Anthy is always going to be at the bottom of the pecking order and will suffer the same unbearable pain by getting used, abused, and stabbed by the Swords of Hate over and over again. She’s seen what Anthy was, she’s seen who Anthy is, and all Utena feels is unwavering love and a desire to free this person from her suffering. At the very end, Utena does and does not save Anthy. Even though Utena herself couldn’t pull Anthy out of the cycle, it’s the act of reaching out to Anthy and offering her hand that gets Anthy to find the strength to leave on her own. The idea that someone has seen her for who she is and still reaches their hand out to her is what convinces Anthy she doesn’t have to be a princess or a witch anymore.

The Saki/Kyoko dynamic, however, is one I have to wonder represents the way it would’ve gone if Utena had failed to see the person Anthy truly was. Saki’s entire motivation during “Witch Hunt” is to rescue Kyoko from this predicament she finds herself in because they were best friends. We’re never told how and why they lost touch with one another after middle school, but by the time they reconnect the two carry the assumption they haven’t changed. To Kyoko, Saki’s a strong, cool, sharp witted prince. To Saki, Kyoko is wonderful, caring, and friendly. Even when Kyoko ominously states she HAS changed, saying “You never know what fate will bring people,” Saki insists Kyoko’s the same as she’s always been. Kyoko doesn’t know how many people Saki’s seen die before her in the three years since their last meeting, and Saki doesn’t know how much Kyoko’s suffering because her illness has destroyed the future she hoped for.

Saki and Kyoko are both motivated by their preconceived notions of what the other is like, and that allows Kyoko to manipulate Saki until the very end. Kyoko sets up everything so Saki will follow the line of logic pointing towards Kyoko as Etsuko Muto’s killer, but Saki believes so firmly in Kyoko’s inherent goodness it allows Kyoko to get the now dead Etsuko to take the fall. I can’t believe my kind friend would do something like this, it makes more sense she’s protecting the real killer because that’s the kind of person she is. Neither girl realizes the other truly has changed, though Saki more subtly. In the past, Saki would’ve probably taken everything at face value and settled on Kyoko getting Mitsuhiro as the end of the story. But after all the time she’s spent as the Sukeban Deka, dealing with monsters like Remi Mizuchi, Saki’s instincts make her realize things are off and force her to confront the kind of person Kyoko’s become. Saki settles for making passive-aggressive declarations of knowing the identity of the one pulling the strings on this horror show, trying to make Kyoko feel guilty or fearful enough to turn herself in. Sadly for all involved, Saki cannot let go of the person she knew Kyoko to be. She wants Kyoko to go back to being that person and to remember what that person wanted to be. She keeps holding onto that image even after she stops Kyoko from killing Mitsuhiro in his sleep, and her taking Kyoko’s promise to turn herself in at face value is what leads to Kyoko’s suicide. Because Saki could not truly and fully see the person Kyoko had become, holding onto the image of who Kyoko once was, Saki failed and Kyoko died. The thing that really digs the dagger in is Saki doesn’t outright tell Kyoko any of this until it was far too late, as she holds onto the old image of Kyoko she kept hoping she wouldn’t need to say it.

What we’re seeing is the way Revolutionary Girl Utena may have ended if Utena Tenjou held onto her childish beliefs and continued to hold up the image she constructed of Anthy to boost her ego. Because Utena could see and accept the real Anthy, that’s what allowed Anthy to leave into the real world. Because Saki could see but could not accept the real Kyoko, that’s what led to Kyoko’s death even with the cancer destroying her body.

I honestly have no clue if Sukeban Deka was an inspiration to Chiho Saito, Kunihiko Ikuhara, or anyone who worked on the Utena anime. Ikuhara does reference it in his current work, Sarazanmai, though, yet it’s no indication if he was aware of Sukeban Deka while working on Utena. Maybe it says something about how these themes are buried so deeply in our subconscious that the ways in which they manifest through different works are sometimes more blatantly similar than we realize upon completion.

Note: This article was originally posted to Comicosity and is reproduced here with the author's blessing!

|