It's a hosted interview between Kunihiko Ikuhara and Mari Kotani, a science fiction critic and translator. The article was translated by the absolutely amazing Youzicha (link to Tumblr), and I decided it needed from there a page deserving of its status as a really unique and unusual piece of meta that, so far as I know, would have just disappeared aside from this effort to dig it up! It's a fantastic look at not only Ikuhara's background, but also the influences around him, and how his work is regarded and discussed in Japanese academia...a thing we have precious little exposure to.

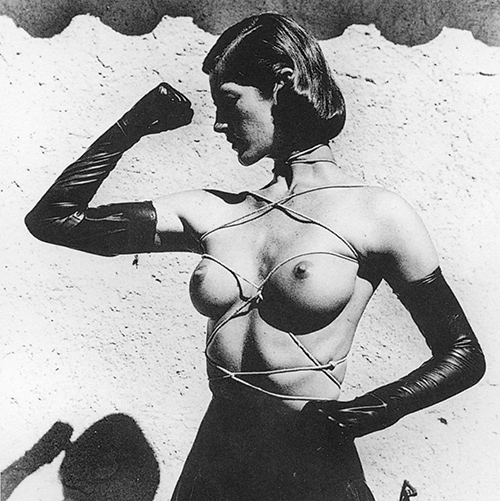

The images I've left intact, with occasional nudity, so head's up there. Anyway, welcome to Actual Sexuality! And again, thank you so so much, Youzicha! -Giovanna]

From the 60's to the 90's: The Phases of Sexuality

— I would like to discuss the representation and development of sexuality in animation, manga, and science fiction. Kotani has written many works that discuss animation, manga, and science fiction from a perspective of gender theory or sexuality. Ikuhara has directed the Sailor Moon and Revolutionary Girl Utena animes, and in 1999 a Revolutionary Girl Utena movie was released. The story of Revolutionary Girl Utena turns around the relationship between Utena, a girl who has decided to become a prince, and Anthy, a girl called the "Rose Bride". I felt it was wobbling mix-up of sexuality. What do you think?

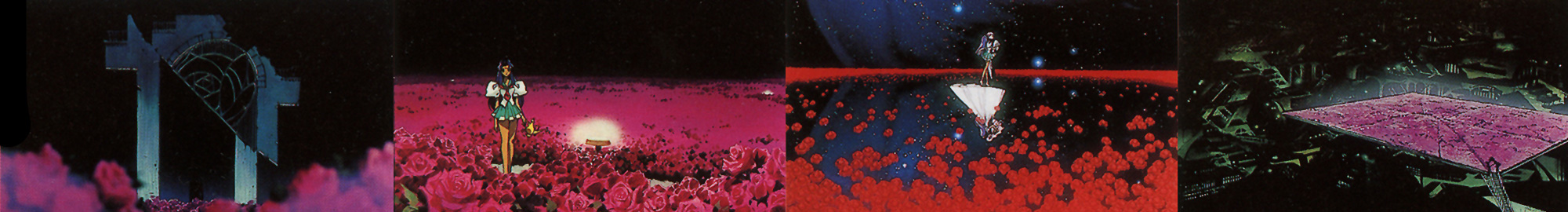

Left to Right: Rose motifs, the Shadow Girls, and Shinohara Wakaba

Ikuhara: Speaking of sexuality, after Utena I wrote a novel which features lots of hermaphroditic characters. It's a collaborative work, a book called Schell Bullet.

Kotani: It is a fantasy world?

Ikuhara: It's a future world. Humanity has divided into roughly two groups, Majors and Minors. Because of gene manipulation the Majors are hermaphrodites without male/female sexes, and they have a monopoly on good genetic material. The Minors are humans who have fallen away from the monopolized gene material, they look basically the same are present-day humans, and have two sexes.

Kotani: Sounds interesting! Are the Minors kind of like slaves, like in The Human Livestock Yapū?

Ikuhara: It's not that they are divided into Major aristocrats and Minor slaves. It's just that in society it is generally understood that Majors are more competent workers. Although in reality that's not necessarily always the case... In terms of our society, it's like which university you went to.

Kotani: Identity must be different for hermaphrodites and for people with fixed sex?

Ikuhara: Even though they are hermaphrodites they are still attracted to either women or men, and categorize themselves as "mister" or "miss". In Schell Bullet, the most outstanding Majors are typically female. It seems that visually I prefer women (laugh). Because I think it's more beautiful when the body silhouette has clear contrasts (laugh).

Kotani: I see (laugh). So, in this world-view, does the fact that people are sometimes divided into sexes and sometimes hermaphroditic have any kind of social, structural significance?

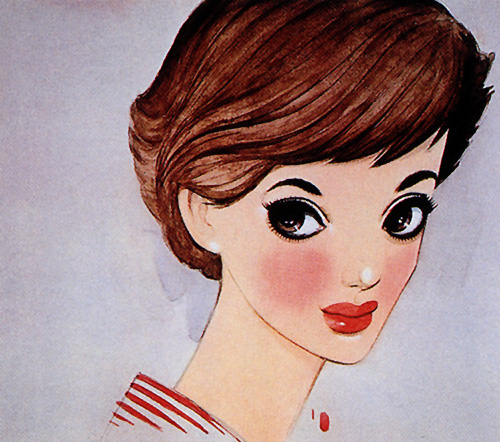

Jun'ichi Nakahara, Cover of 'Soliel' Magazine, June of Showa Era Year 33 (1958)

Kotani: So does the story develop into, like, a sexual adventure for the main character?

Ikuhara: The story begins when the main character gets a job at a space trading company. When they hire him he claims to be a Major, but his boss discovers that he is actually a Minor. In the end, he comes to a special agreement with the boss, and continues to pretend to be a Major.

Kotani: He pretends to be a hermaphrodite. Concealing his true nature, how interesting. But, to think that someone is a hermaphrodite and then discover he is a man, that feels kind of erotic, right? (laugh)

Ikuhara: The boss is visually female, a Major with a very bold beauty. From the start I wanted the main character's boss to be a hermaphroditic woman. That's because, the way I see it, even the Major women in the real world, that is to say women who are competent workers, seem to have an intense male side. The bosses appearance is that of a sublimely beautiful woman, but her words and actions are male, and she uses far more cruel violence than the main character. He is afraid of her violence but at the same time drawn to her, and can't resist his feelings (laugh).

Jun'ichi Nakahara, "Snow White" (Kodansha "Jun'ichi Nakahara Art Works")

Kotani: What a startling story, I'm surprised! This is the kind of story that a feminist female author would have written in the old days, but now in the 90's, male authors have started to write them. I have heard of several examples this year. Rather than the womens' sexuality shaking, now it seems it's the mens' sexuality that is shaking. When I wrote my criticism of Neon Genesis Evangelion (Evangelion as the Immaculate Virgin, published in House Magazine), several readers commented that they would like to see Revolutionary Girl Utena written about in the same way. So then I watched Revolutionary Girl Utena. I was keeping Evangelion in mind as I watched it, but my impression was quite different. First, the drawing style was like shōjo manga, which felt a little nostalgic. It had a kind of Soleil-magazine-style atmosphere, like Jun'ichi Nakahara or Makoto Takahashi.

Ikuhara: Ah, we really paid attention to that. I told the staff at the beginning of the production that is the kind of nuance that we have to bring out.

Kotani: For example the rose motif, or the shadow girl silhouettes, or in particular Wakaba Shinohara's figure as we watch her from behind, they have an atmosphere which is really similar to drawings from that era, don't they?

Ikuhara: Ah, they do. I really like Jun'ichi Nakahara, so I referenced his work a lot.

"Velvet Goldmine" (1998) The underground culture of the 60's became mainstream in the 90's.

Japan Herald © velvet goldmine productions ltd/newmarket capital 11c mcmxcviii, ¥16,000 (tax not included)

Another thing... I heard you like Shūji Terayama?

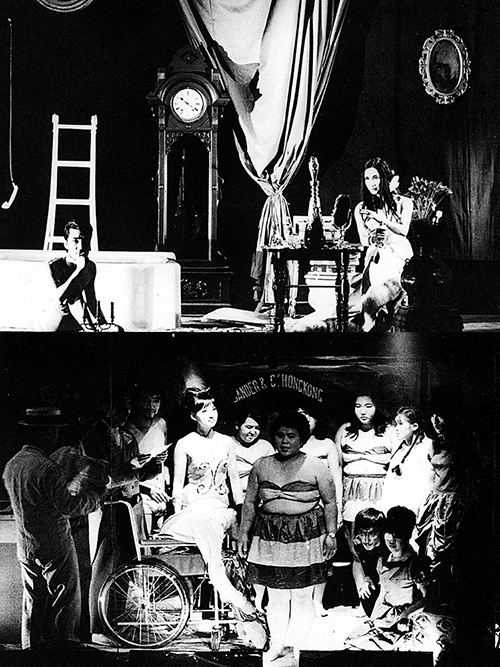

Top: 2nd performance of Tenjō Sajiki/Shūji Terayama's "The Crime of Fatso Oyama" (1967)

Bottom: 3rd performance of Shūji Terayama's "La Marie-vison,"" Marie played by Akihiro Miwa (1967)

Ikuhara: I really liked Terayama. When he died it was a great shock. But in terms of his artistic career, when I found him it was in Terayama's last period, when society had begun to treat his works as culture.

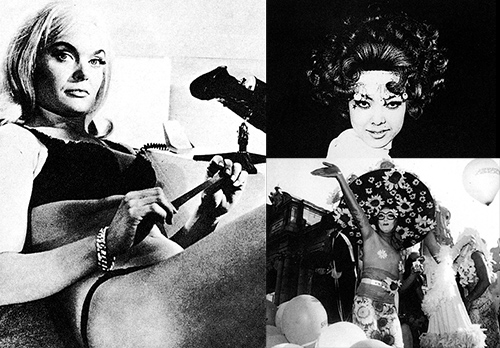

Kotani: In his first period he was extremely avant-garde. The world that Terayama himself created is also extremely interesting, but for me, I was first interested in the generation of creators that Terayama influenced, and then backwards from there I learned about Terayama's world. In particular, when you investigate the sensibilities of bondage- and queer creators in the 90s, the roots lead to the late 60's and early 70's. There existed a "camp" culture which could include things like Peter, or Akihiro Miwa, or lesbian-ish stuff like Jun&Nene. I think you can see its cultural influence. I think the time from 1965 to the early 70's was a rather special era, with a very distinct character.

Ikuhara: Around 1970, those things were still out of the ordinary, right? For example, girls like the Bond girls in 007, who would ride motor bikes and fire machine guns and behave extremely masculinely, were out-of-the-ordinary and therefore trendy, but in the 90's girls who behave masculinely are not unusual at all, so media have ceased to especially promote them.

Left: 007 :Goldfinger (1964) Pussy Galore

Top-Right: "Funeral Parade of Roses" (1969) Director Toshio Matsumoto

Bottom-Right: June 29, 1996, Madrid 「gays and transexuals parade」

Ikuhara: Terayama's words are interesting too, but what I find the most kitschy and cool is his theatre. Suddenly a completely naked actress would appear, without even a genital cover, and this was in Kinokuniya Hall! The police might barge in saying "Hey, wait a second". I guess this is why they say it's a fine line between a hero and a criminal (laugh), but until then I had never thought that showing your panties or showing your willy could be anything but shamelessness, and now the Asahi Shimbun was treating it as superb culture. I found that gap extremely mysterious and fascinating, and personally I felt a cultural nuance there.

Prince and Princess: The Composition of an Illusion

*When she was a little girl, Utena Tenjō met a 'prince', and admired him so much that she decided to 'become a prince' herself. She transfers to Ōtori Academy, where she encounters Anthy Himemiya, a girl known as the 'Rose Bride', and student council members known as 'duelists'. The 'duelists' are an elite that have been chosen by the 'End of the World' and possess the right to be engaged to the 'Rose Bride'. In order to be engaged one must win a duel. Utena wins the duel and becomes engaged to the Rose Bride Anthy, but new challengers keep appearing, and each time Utena faced trials, struggles, and worries. In truth, Anthy is the sister of the director of the academy, Akio Ōtori, and Akio is both the prince that Utena once admired and also the End of the World. And supposedly, the person who controls the Rose Bride Anthy will obtain a power to revolutionize the world...*

The stage-like compositions of "Revolutionary Girl Utena ~ Adolescence Apocalypse"

Ikuhara: Well no, I'm often told that, but actually I wasn't thinking at all (laugh). Somehow, I just felt I wanted to make it more naughty than the TV series. That's about all that I thought.

Kotani: Indeed, compared to Utena and Anthy in the TV series, in the movie they tangle more directly. That surprised me a little. In the TV series, they will know each others' secrets, and still look innocent and calmly eat breakfast together, and lightly stab at each others' secrets by exchanging meaningful phrases. There are a lot of 'hinting' scenes.

— A girl who admires a prince is a common pattern, but to admire him so much that she decides to become a prince herself, I think that needs a mental jump?

Ikuhara: Girl characters in anime are generally tomboyish or masculine. That is, if they are the main character. Even the "ordinary person who gets caught up in events against their will" type of protagonist, once they are put in the middle of the giant battle which will determine the course of history there's no way they can be feminine. Typically such stories gradually move the heroine from her peaceful everyday life into an out-of-the-ordinary masculine community. Like, an ordinary girl gets summoned to a *isekai* world (laugh). And at the end, she has changed the course of history... even though that is a masculine role.

What I tried for Utena was to start by having her say "I'm going to become a prince." I made her a person who herself is aware that her character is occupying a masculine position in the story. Although, at some point she finds herself in a feminine position (laugh).

Kotani: What a paradox!

Ikuhara: And therefore, she faces trials as a prince over and over again.

Kotani: That makes sense. They call her a tomboy, and still...

There are certain recurring patterns to the duels; Utena appears to be fighting, but in reality she is not. It's rather as if the people who enter each have their own problems, they use the duel as a way to resolve them, and the opponent happens to be Utena. So it is as if Utena serves as a stand-in for the things they need to overcome. Utena is there as a kind of aspiration—maybe you can compare her to the straight-man character in a *kyogen* comedy. It feels like she is a medium that can be formed into whatever objective they need to overcome.

Ikuhara: Maybe she's a prince-as-illusion. Because Utena is a woman, one understands visually that she is a prince only as an illusion. And from the very beginning, all the characters realize that the prince is nothing more than a dream. I thought that was interesting.

Kotani: The illusions support each other: is the prince required because there is a princess, or is the princess required because there is a prince? It's a condition where we don't know clearly which illusion came first. And to demolish the fact that this structure itself is the illusion, they keep venturing into various situations over and over. I feel like you are analyzing and investigating prince-princess fairy tales extremely closely.

You once said that Utena is a girl who has a romance, but that there is a difference between "romance" and "romantic".

[Translator's Note: ロマン "romance" as a loanword in Japanese can mean something like a near-impossible dream, a great undertaking, or an epic adventure.]

Ikuhara: "Romantic" has become a word for girls, and "romance" basically a word for men. In short, "romantic" is something that comes from the other. Like, I'll make you into a princess, or I'll arrange a wedding at a wonderful location; it's a world which a prince will appear from and return into. While "romance" is something like venturing into the trackless wilderness, that kind of world.

Kotani: Even the words themselves are gendered into a word for men and a word for women?

"Revolutionary Girl Utena" (TV) The Prince on the battlefield.

Kotani: I thought of it in the opposite way. That the "end of the world" is something which has been driven away to the borderlands, as opposed to the system which occupies a central position. In other words, I thought it meant those who deviate from the center.

Ikuhara: I treat those as synonyms. It's a world where, the further you try to reach, the further you are driven away. If you take a romantic stance, you don't particularly need to know about the system which confers the romantic situation on you. But if you try to maintain a romance, you need to know the system or structure of the situation. The romantic is something which "comes to you", but for the romance, if you take a passive role you will not obtain it. To obtain it you must necessarily involve yourself with society. In other words, you must necessarily involve yourself with reality. But when wishing for a romance, I think everyone begins with a dream. As you try to reach that dream, you become aware of more and more problems and begin to understand the big picture. That is the psychology of someone who has reached "the end of the world", who has become a boring adult. The Academy Director, Akio Ōtori, is someone who saw the "end of the world", understood it all, and despaired—in other words he became a boring adult.

— Indeed, the prince in the TV series (Akio) despaired, and in the movie the prince is dead and Utena and Anthy exit into the trackless lands. Why is the prince dead?

Ikuhara: Well, there are no princes in the world today, right?

Kotani: Really, there aren't? (laugh)

Ikuhara: Are there? I don't know, but I think in modern times there probably aren't any. Considering how news and media have progressed in this era, it would be difficult. Princes are basically patriarchs. In the old days, they were people like Shigeo Nagashima or Yujiro Ishihara. Nowadays there is nobody like that. Even Kimutaku (Takuya Kimura) is a bit different. It feels like this depends on the era. Even in ancient times princes must have been an illusion, but they existed very far away. It used to be that people who were only promoted in media were at a long distance. But current stars like Kimutaku, well of course Kimutaku himself is still far away, but the illusion that he has, you can sometimes see that same illusion in some man sitting next to you.

Kotani: Maybe this is a hard era for princes to live in, but it feels like it is still full of princesses. Lately I have started to think that the princess illusion is stronger, or perhaps I should say, that the boys are princessifying.

Ikuhara: Maybe so.

Kotani: They are raised so preciously, and so they, like, take a passive role; they have an illusion that happiness will come to them. Like a princess who believes that her prince will come for her, these boys believe that some wonderful thing will come to meet them.

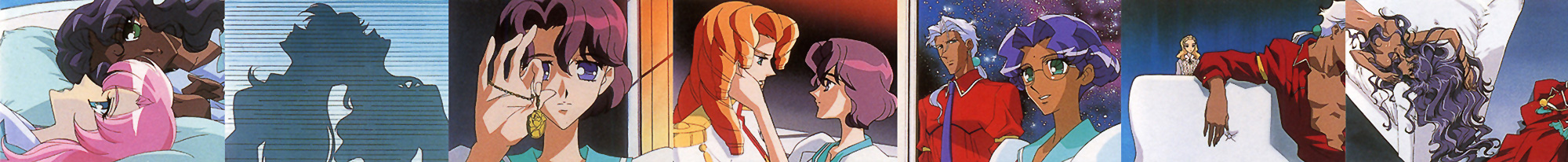

Left to Right: "Revolutionary Girl Utena" (TV) Utena & Anthy, Juri & Shiori, and Akio & Anthy

The Girls Who Survive: Being Driven Out of the System

*The story progresses by characters visiting Nemuro Memorial Hall to confess their traumas and worries.*Kotani: In the middle part of the tv series is the story of the Black Rose Society (Nemuro Memorial Hall). It's stylized, weird and creepy. Personally, I really liked that part.

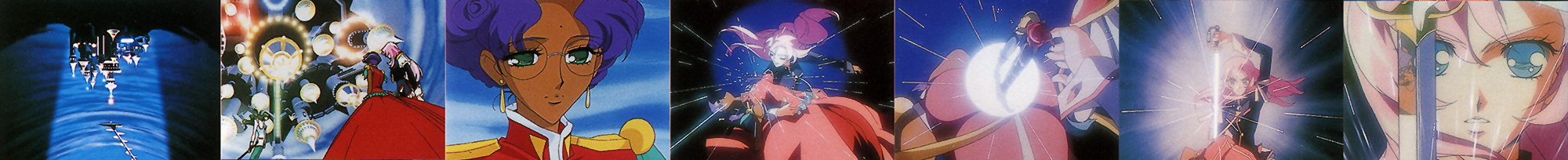

Ikuhara: That's something women like. That part was difficult for me though.

Kotani: I thought the stylization was really excellent. There's the arrow symbols, and the confession in the elevator. When the elevator stops, there is a morgue-like place, with jumbled rows of coffins. It feels dark and mysterious. You know, I like bondage stuff (laugh). Basically, I like deviation, I want to escape away, but if you are not oppressed there is no way to escape. In order to deviate, you have to first be tied up. The Black Rose Society particularly emphasizes that, doesn't it? You have some worries, so first of all, someone will slowly look them over. Places of surveillance as places of bondage—e.g. a military unit, a monastery, or a dorm becomes an excellent stage setting, right?

Ikuhara: I like it too. But by deviance, do you mean sexual deviance?

Kotani: Deviance from the system. A community with rules, where there is someone like a dorm supervisor who runs a tight ship, and you escape from it.

[I translate 逸脱 as "deviance"/"deviate", but 脱する means "get out, escape" so when Kotani links deviance and escape she draws on that connotation.]

Ikuhara: There's sexuality there, right?

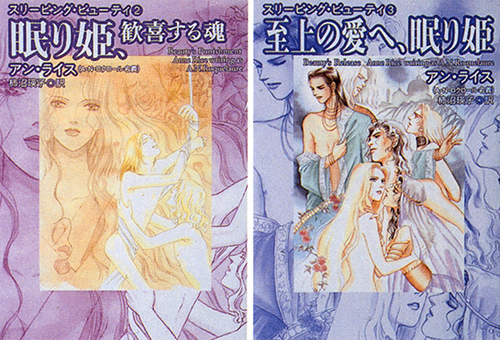

"Sleeping Beauty" Volumes 2 (top) & 3 (bottom)

In the fairy tale the prince goes to save the princess with a kiss, happy ending, right? However, in the first volume of Sleeping Beauty the way the prince wakes up the princess is not by a kiss, but by taking her virginity, and then he brings her straight back to his own castle, which is an S&M dungeon ruled by his mother, the queen. The prince and queen gather slaves from the neighbouring countries, who have to go through a fixed number of years of harsh torture before they are allowed to return home. In short, the story is about how Sleeping Beauty is abducted into a strongman country and gradually becomes a masochist. In volume two, she has become rebellious, and as her penalty she is sent to the "Pervert Village" where an even harsher masochist lifestyle awaits her. In volume three, the Turkish sultan attacks Pervert Village and abducts Sleeping Beauty to his palace harem in Turkey, where she is again put through the masochist lifestyle. At the end, Sleeping Beauty has become the perfect masochist, and also she knows through personal experience how to cause pain so she can act as a sadist as well. Then the prince, who has now turned into a masochist, tries to woo her, but she tells him that she is not suited for the sadist role, so instead of the prince (who is now a masochist through and through) she pairs up with another man who has chosen the path of the sadist, happy ending. The entire story is about all the torture Sleeping Beauty, and also the prince and the queen, take part in as masochists or sadists. And at first sight, it seems to accept the culture that says that the man attacks and the woman is passive. However, if you keep reading the story it is not that simple. The task of torturing the masochists also fall on Sleeping Beauty, and on all the princes and queens from the neighbouring countries. In the story this keeps happening; ordinarily, since everyone is put in a position like Anthy's, you would expect them to hate it, but in fact they don't (laugh). Becoming a complete masochist, if exaggerated a little, also reveals an aspect of deviating from the system. And then this masochistic deviance causes a kind of shift of the S&M system itself to appear in the story. You start to feel that the idea that women have to go through their lives tied up inside the system is shifting slightly, which is paradoxically fascinating.

I think that when female authors want to write about deviation, about jumping out of the system, the form that they choose surprisingly often is stories dealing with the bondage system.

As a concrete example, when you pick two male characters from an existing work (a manga, novel, TV drama, or phenomenon) and depict a love story between them, we call that "yaoi", and it is extremely common for yaoi-stories to take place in schools. Utena is set in a school too, right?

Ikuhara: The reason for that is extremely simple. For girls, places like schools are the only social communities that have any reality to them.

Kotani: Right. It's a world where you can easily see the system that ties people up. I think that's exactly why stories about deviance so often choose such settings. However, when you read books written by women, they are overwhelmingly the type that maintains the status quo, and the idea of changing the world appears surprisingly rarely. For example, back at the peak of the women's liberation movement there was a lot of feminist science fiction written, and I expected that there would be a lot of novels where women take over the world and keep men as slaves, but there's not. On the contrary it seems it is authors with more masculine ideas, or a more masculine way of thinking, who produce stories about turning the world upside-down and creating a matriarchy, and there aren't many such stories. Most female authors instead seem to write stories about creating a better world by starting from familiar places in your daily life and making them more cozy, one by one. But in those familiar places they are stitching up the gaps in the system, changing it piece by piece.

Ikuhara: Is that Eros?

"Revolutionary Girl Utena" (TV) The styles of the Black Rose Saga's Nemuro Memorial Hall: coffins, the entrance, and the visitation room.

Ikuhara: It's shifting the relations?

Kotani: Shifting them only as much as is convenient for themselves.

For example for Anthy, who has ended up in the awful pits of hell, it might mean that she decides to improve herself to make herself think of the pits of hell as a pleasant place. This idea is quite scary, isn't it? I think the reason that the Black Rose Society is popular with women might be related to this mentality. There is God's system, there is bondage, you confess, and then you start by changing only the familiar and nearby, that's what you fight for.

The way boys fight and the way girls fight are very different. And what they fight for. Maybe boys think of fighting as confronting the world at large, to turn over the entire system to create a new world. But girls are not yet at the stage where they fight the world, they have to survive. Because they fight to keep living, they adopt a style where they start with the nearby: let's just make this place a little easier to live in. They always think that if they let themselves get distracted for a moment they will gradually suffocate, and that unless they draw a strict boundary line between themselves and others they will disappear. But if you think about who it is that are suffocating them, it's actually the very nearby and familiar, like their parents or partners.

Ikuhara: Concretely, what is being suffocated?

Kotani: Before she herself thinks "I want to do it this way," she goes "you probably think we should do it this way, right?", constructing her self out of the words of others. It's like continuously being told to perform plastic surgery on your own individuality to align yourself with the social system, like being put into a defenseless state. Even before demanding "I want to do this, I want to have this", it's immensely difficult to reach the point where you are aware that making requests is an option that exists.

Ikuhara: I both feel like I understand and like I don't. I think that women silently wish to be set free, but it is merely a concept, and if it was concretely realized women would find it much less enjoyable than they expected. This is something that I noticed when making Sailor Moon. If there is a social system to say "hey this kind of woman is cute" and coerce women into putting on mini-skirts and jump around to show their panties, then they will be strongly resist it, but if a woman herself takes the initiative to put on a miniskirt, and to suddenly start dancing and swinging her hips in front of a man to show her panties, then for some reason women will applaud and cheer her on.

Kotani: Although at first glance it might seem the same, I think there's a bit of a difference!

Ikuhara: Maybe this is similar to the Sleeping Beauty story we talked about.

Kotani: Right. Maybe the process is the important thing. In the case of the Sleeping Beauty story there is a narrative, and the process by which Beauty becomes a masochist is structured very logically. That process is explained extremely convincingly. But if it wasn't like that, if I read a novel that suddenly said "women are submissives, right?" and started to violently treat her in a masochistic role, I would just get angry. And I would think it was a boring story (laugh). Perhaps by showing the process as fiction, a part of it can be solved.

The Girls' Eros Fantasy: A Negation of Power Structures in Yaoi

Kotani: How did you think about relationships between two women, like the relationships between Utena and Anthy, Juri Arisugawa and Shiori Takatsuki, and so on? Sometimes it is thought of as one girl and her alter ego.Ikuhara: Yes, that's true of course.

The stage-like compositions of "Revolutionary Girl Utena ~ Adolescence Apocalypse"

Ikuhara: But I think what it is expressing is simply yaoi. To do that using shōjo "royal road"-like characters, and with two women, is somewhat rare I think.

Kotani: Indeed, it is really rare for a sexual entanglement of two women to appear openly. In particular, when we find out that the photo in Juri's locket is of Shiori, and that she is Juri's unattainable love interest, I was a bit startled.

Anthy was a really popular character, right?

Ikuhara: I think Utena was more popular, but women seem to particularly empathize with Anthy.

Kotani: At Comiket there were more sex stories featuring Anthy than Utena, but those were all made by women. They draw explicit porn too. I suppose Anthy feels like a person who doesn't exist in reality. That's why she is scary. All those parts that you usually put a lid on and don't want to see, Anthy has them. A different character's stepmother turns out to be Anthy in her red dress (in the TV series episode 26), that was really scary! Something Anthy-like suddenly appears.

Ikuhara: Right, it's scary! (laugh) The production staff were also super excited about that part (laugh).

Kotani: For example, in terms of the relation to Akio, during the time when Akio found despair and knowledge, Anthy was constantly plagued by the million swords. And therefore, no matter how dainty her smile is, it looks like a smile of despair. You can't smile like that unless you know the very pits.

Ikuhara: I guess Anthy being in the victim position makes her easier to empathize with.

Kotani: But in relation to Akio, at the end you can no longer tell which of them is ultimately the victim.

Ikuhara: Surely Anthy is still the victim? Even she herself realizes that she is a victim, which is scary. [*] Although Anthy and Akio are siblings, it's very clear that inside the family they have a father-daughter relation, which makes this easy to understand. The family system is what ties you up, the family system is also what creates morals.

[* Or "even he himself realizes she is"? I'm not sure who the pronoun refers to.]

Kotani: Akio is there as a stand-in for an Oedipal patriarch.

Left: Akio leaping over the car.

Right: Three boys frolicking on the car.

Kotani: Anthy and Akio is incest, so there is an understanding that they are doing something extremely wrong, but at Comiket there were stories where it is Akio who is trapped by Anthy. And stories where Anthy is not just unilaterally being abused, but conversely is controlling Akio. I thought that is a bit *gekokujō*-like. And some dialogue like that actually happens in Akio's dreams, right?

Ikuhara: Akio says - I'm the one who is being controlled, I'm the one who is being tortured.

Kotani: That is the same pattern as the power relations in yaoi. In yaoi, if for example there is a pretty boy and and old man, then the man will tie up/imprison/rape the boy. An old man tying up and raping a young boy is about the same as the relation between men and women— that's how it is depicted. But then, the man who supposedly controls the boy might suddenly go sexually crazy and take the boy with him and run away. When that happens, the system itself is no longer preserved, the two men are deviating away from the system. Or in the middle of the story, the man who was in control might have his life ruined by the boy, in a reversal of the power- and superior/inferior-relations.

There is a yaoi-themed magazine for women called June, it's published by the same company that publishes the gay magazine Sabu. Once they let authors from both magazines compete to produce a joint magazine called Roman June. Strangely enough, when you read it the stories written by men and women divide very clearly into two types. The ones with a structural reversal, where the man who was in control later has his life ruined, were almost all written by women. And on the other hand, the ones where he keeps endlessly abusing and taking advantage of the weaker party were written by men. Among the ones I read, this division into two types was surprisingly extreme.

Ikuhara: To say it explicitly, [sentence I didn't understand], women have a stronger awareness of being controlled by some kind of system.

— To give an example, maybe it's like this: if Misato or Asuka from Neon Genesis Evangelion rapes Shinji, that's yaoi, but if Shinji rapes Misato that's simply porn. You don't have to invert social classes, it's sufficient to negate the idea that the woman is the passive party. I think that's the entirety of yaoi. Don't all the popular characters in anime inherently have that in them? For example, there's a Dragon Ball character called Vegeta. In the beginning he was a strong masculine character without much of a following, but then he kept losing fights, and each time he went "shit! I was defeated!", feeling sorry for himself. And at that point women suddenly started to like him—"oh, Vegeta was a submissive character after all!" (laughs) He got super popular the moment he turned from being a *seme* (the masculine role in the sex act) to being an *uke* (the feminine role in the sex act).

Kotani: I get that, I think that's the number one pattern for popular characters. The characters that become *uke* are quite often the baddies.

— There's a question of reading skill among the girls. The girls whose yaoi antennas are not yet sensitive favor pretty boys, but when their skill level increases, then the moment when a *seme* character turns into an *uke*...

Kotani: ...becomes erotic. Although, here's a different story. Captain Tsubasa is another manga which was extremely popular in the yaoi world in the 80's, and the most popular pairing was between the feminine-looking goalkeeper Wakashimazu and the baddie Kojirō. And supposedly there raged a fierce argument at Comiket about which of them was the *seme* and which was the *uke*. Should the rascal Kojirō be twisted into the *uke* role? Or, following appearances, was the already girly-faced and long-haired—that is to say feminine—Wakashimazu the appropriate *uke*? The former faction negates traditional gender conceptions, while the latter faction, one could say, affirms them—or at least they are people with a stronger conservative tendency, they are basically satisfied by just the small change of having a male-male romance. The former faction will not be satisfied until they have gone all the way to turning around the gender roles. But as it turns out, in the end the two factions reached as peaceful resolution based on height difference. Shōnen Jump published a chart of the height of all the characters, and it turned out that Wakashimazu was taller than Kojirō. And at that moment the entire Wakashimazu-*uke*-faction, who had reproduced the traditional gender conception where the girly character is the *uke*, reversed course to say that Kojirō makes a far better *uke*. In this incident one can clearly sense that those who reproduce traditional male/female gender roles through yaoi can only accept that the taller character is the *seme*, i.e. the male role.

And so Kojirō became an outstandingly popular, thoroughly *uke* character. How much *uke*? They had him raped, or selling his body to get out of debt, or being locked up in a house somewhere to be kept as a pet. It might sound strange that such a bad-guy character would be so emasculated, but it makes for very fun reading to "twist" someone into an *uke* character.

— Emasculation is good, huh?

Kotani: Right, it's erotic.

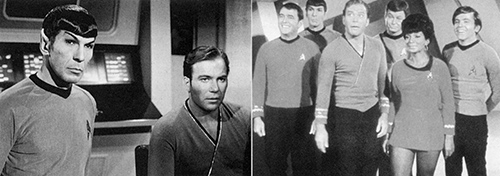

"Star Trek," © Paramount Pictures 1991 (Aired 1966-69)

Kotani: In the west there's yaoi of Kirk and Spock from Star Trek. There are others, like Starsky & Hutch and The Man from U.N.C.L.E., but Kirk and Spock is most popular. And, although it's not a romance between two men, there are parodies of the Beauty and the Beast TV series.

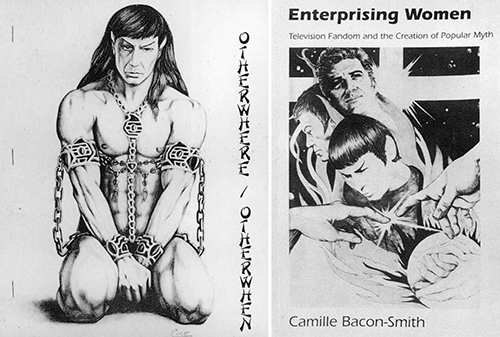

Left: Cover of "OTHERWHERE/OTHERWHEN" ('Star Trek: An Alternate Universe' K/S Fanzine, by Marilin Cole)

Right: Camille Bacon-Smith, "Enterprising Women"

Kotani: Yes, almost entirely by women. But the points they care about are a little different. Because these are male-male and the content is very pornographic it seems the same as Japanese yaoi, but I have never heard of Americans fighting over which character is the *seme* and which is the *uke*, like Japanese do.

So I investigated a bit, and although in Japan people have an interest in *seme/uke*, particularly in *uke*, in America it shifts into more racial problems. Spock is half alien, so his features are exotic. Apparently that's felt as something very erotic. Also, Spock is portrayed as an alien, and he periodically becomes very sexually uninhibited, he sexually cannot stop. That concept is in the original Star Trek. And to help Spock's sexual suffering Kirk will offer his body. Kirk is the captain and Spock his junior officer, but when this time comes the power relation turns over, the American girls find this exotic. Which means that there is a *gekokujō*-like world here as well.

Ikuhara: The case of Japan is easy to understand, right? As soon as you see the destination point of producing children, sex becomes a social system. People don't like that, and that's more or less the entire explanation. In yaoi there is sex, but there are no children. In reality it is not possible for sex to only function as pleasure, so you can understand that people are drawn to that unrealistic part. But what about America?

Kotani: They are interested in the non-human, in an existence outside the human, which is to say the white male. The pattern where Beauty's partner is the Beast is also popular.

Ikuhara: Maybe they really have that concept of forbidden sex. For us, that's a little hard to understand. We feel, "forbidden sex, what's that?" This must be related to religion, right? In the end it's a purity ideology. White people are surrounded by white people and black people are surrounded by black people. Religion is a fundamentally a purity ideology, so there is a fight between the terror of straying from purity, and on the other side the simple curiosity of wanting to enjoy pleasure, the sexual desire, isn't there?

"Lawrence of Arabia" (1962) Peter O'Toole & Omar Sharif

Ikuhara: That's makes it easy to understand. Women particularly like that story.

Kotani: They told me that the relation between the characters played by Omar Sharif and Peter O'Toole is close to the Kirk/Spock relationship.

Where the Boys' Eros Went: Beautifully Dressed Men

— Through yaoi there has developed fantasy stories which are closely connected with women's Eros, but what about fantasy connected with men's Eros? For example, any anime or similar that presents a male Eros fantasy?Ikuhara: I haven't watched everything so I don't know, but if by works that let you feel sexuality you mean visibly erotic works, then lately nearly everything looks like Eros fantasies. Everything from children's media to works targeting the high-teens. In terms of design, I think a lot of fictional material relating to sex is appearing. Although of course the personality of the voice actors has an influence, anime is fundamentally something deliberate. It is produced deliberately. But despite that, I can vaguely feel a tendency. It feels like it has entered in more or less all anime, the visuals of Utena included.

"GTO (Great Teacher Onizuka)" by Tooru Fujisawa (Weekly Shounen Magazine J)

Ikuhara: Speaking in turns of general tendencies, if you compare a picture from a 20 year old anime to current anime, they are completely different. The "vulgar" characters [*bankara*] from the past and now are unmistakably different. If you compare the media depictions of the protagonist from Otoko Ippiki Gaki Daishō and the protagonist in Great Teacher Onizuka, then the one from Great Teacher Onizuka is more androgynous, or even looks feminine. It feels like in the past, the Great Teacher Onizuka protagonist would have been a female character design.

Kotani: Indeed. The things available to watch are becoming extremely erotic, extremely sexual. This is easiest to see if we consider yaoi. Yaoi first developed around 1970. Not just in Japan, it developed in the U.S. around the same time. When I asked why yaoi suddenly emerged in that time period in Japan and the West, I was told that "that's the time when beautiful-looking men first appeared". Exactly then, rock stars started to make world tours. Until then, men had never been an object to look at. Or if they had, they had not been looked at the way women are looked at, but for example their image was to be seen a symbol of strength. Then a number of stars appeared who were looked at in the way that girls are looked at, as an object to be consumed. As media developed, this tendency of boys as consumption objects grew wildly from the 70s onwards.

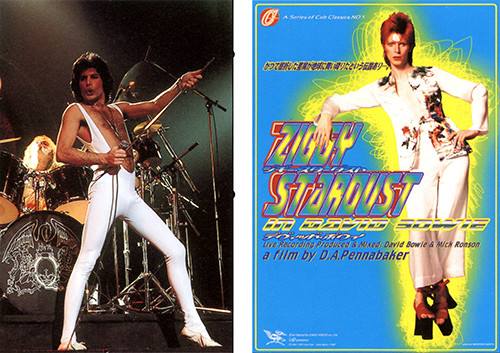

"Velvet Goldmine" (1998) Japan Herald © velvet goldmine productions ltd / new market capital 11c mcmxcviii, ¥ 16,000 (tax not included)

Left: Queen © Richard Aaron/IPJ

Right: David Bowie as Ziggy Stardust

Ikuhara: It's fine to interpret it that way. But I think I made it thinking "this is 'hobby'". Wanting diecast car models, wanting Chogokin toys, wanting a Lamborghini Countach, wanting a Ferrari. Or in the end, to want "the world", these are all "hobby". In the minds of boys who want "hobby", even girls don't exist as more than a "hobby". But it feels very sad to put away every behavior that tries to realize a dream under the word "hobby"! (laugh) For example, I think the things that Steve Jobs say are also basically "hobby". The desire to rule the world of personal computers using your own sense of aesthetics, as a story that's very cool and full of romance, but if you examine it more carefully you'll find it's the "hobby" world. He wants toys that rule the world.

Kotani: The "hobby" world is like, the pleasure of possession.

Ikuhara: As a man, I try to avoid realizing when what I'm doing is "hobby" (laugh), and just try to advertise how hard I work, probably... The things I want are no different from Chogokin and Countachs. So when I talk about how I struggle and how I labor, and then a girl just instantly says "in the end, you just want toys" that really hurts (laugh). We talked a lot about romance, so this is like flipping over the table— but in the end, no matter how much they speak of romance, the things men really want is nothing more than that. That's the saddest part of being a man, I think. Conversely, I feel like girls don't really have "hobby". For example, boys might want Sailor Moon dolls too, but in that case it's only because they want to to collect them. That's "hobby". But girls think about how to play with the doll, combing the hair or changing clothes and so on. Psychological projection.

Kotani: It becomes an action, a process.

"Revolutionary Girl Utena ~ Adolescence Apocalypse" Movie: Anthy rides Utena into the wilderness.

Kotani: It is becoming a little bit unisex?

Ikuhara: I don't know how to express it, but for example, because your house shows your aesthetic sense it has a component of projection, but men might say "once I have made a lot of money I will get a really big house", and they will not care very much about style. They just think the bigger the better. Whereas women, I feel, care a lot about the style. Men treat houses as "hobby" too. A toy that you possess.

Kotani: For women, maybe living comfortably is important. Because that's survival.

Ikuhara: For women, how they live is important, but for men the living is less important than the owning.

Kotani: Possession versus action. Possession versus process?

Ikuhara: In that sense, I'm extremely interested in the psychology of men who project themselves into something, or want to become one with something. Because I myself feel fed up with this "hobby" inclination (laugh), I would like to get a different value-sense, but it is difficult to escape from the desire for possession, the desire for control.

The value-sense of men who have escaped from those are a bit different from women, I think. The men who come closest to what I'm imagining are perhaps race-car drivers, or ballet dancers, or dancers in general. For example, the moment when a race-car driver drives super fast and becomes one with his car. You could say that exactly that moment is beautiful, or exactly that condition of becoming one is beautiful. You often see that with women! For example, the moment when a figure skater dances is beautiful. That's extremely alluring, but men are almost never seen in that way.

In the situation when a racer drives super fast, the man and car become one. I don't know if he himself is conscious of it, but in that moment only, I feel that it's not "hobby". Men are creatures who live their lives thinking. If they stop thinking they cease to be male. But in that moment of super fast driving he can only think of life and death, it's a world of only reflexes. When you escape from the world of thinking, that moment when you forget "hobby"...

— You can feel Eros?

Ikuhara: I don't know if it's Eros or not, but I'm super interested in it.

Kotani: It feels like in such a situation, instead of thinking, you become one with your body. You move to a place where you are not objectified, a place where you can see yourself.

Ikuhara: Maybe so. In any case, I'm super interested in the idea of becoming one with "hobby" (laugh).

— Is men doing body building something completely different from women dressing up? In body building, you are making a hobby of your own body (laugh). You are "thing-ifying" your body.

Kotani: As opposed to making a "thing" the object of hobby, what about becoming one with the "thing", becoming the "thing" itself?

Ikuhara: That's a world unique to women, that men don't have. So when I wonder if men are creatures who cannot live without "hobby", I feel really demotivated (laugh). If all my ambitions and efforts turn out to be just an effort to obtain "hobby", that's really depressing (laugh). That's why, as a fantasy, I made Utena venturing for "the end of the world" be a woman, there's an assumption that since she is a woman she is not fighting because she wants "hobby". Even if I'm projecting myself into the character, I can lie and say that the goal isn't "hobby"; that's a huge relief and really saved me. If she were a man, then even if I said that the goal wasn't "hobby" I would not be able to find a reason to justify that claim.